Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction Technologies

January 29, 2026, 10:34 am

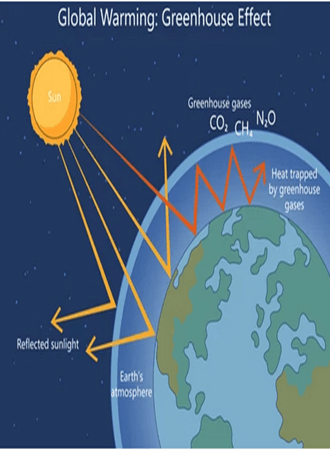

The agriculture sector is recognized not only as a contributor to Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions but also as a potential source of solutions.

Greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture, primarily methane (CH₄), nitrous oxide (N₂O), and carbon dioxide (CO₂), arise from a wide range of activities, including enteric fermentation in livestock, manure management, rice cultivation, fertilizer application, and land-use changes.

Livestock Farming Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Livestock farming has always been a huge emitter of greenhouse gases. For example, as far back as 2015, livestock systems emitted some 6.2 Gt of CO2eq, comprising 12% of total anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Cattle account for about 62% of livestock emissions, much greater that the combined sum of those from buffaloes, sheep, goats, pigs and chickens.

The OECD suggests significant reductions in livestock’s carbon footprint are achievable through targeted actions and investments. For instance, rumen modification (e.g. feed additives that reduce methane) and selective breeding for lower-emission animals can markedly cut emissions from enteric fermentation, which constitutes two-thirds of emissions from meat production.

Enhancing productivity is also crucial as it increases the amount of meat produced per animal (through better genetics, health, and feed) and means fewer total animals are needed, which in turn lowers overall emissions.

This is because emissions are closely tied to the size of animal inventories. Raising productivity per animal allows meat output to grow while keeping herd sizes (and thus emissions) lower than they would otherwise be. This has significant potential to improve management practices, particularly in low- and lower-income countries where productivity is low and livestock populations are large.

However, it is important to distinguish between measures that can be implemented immediately and those requiring sustained investment and further development. In many countries, basic prerequisites–such as access to quality feed–may be lacking, limiting the applicability of some strategies.

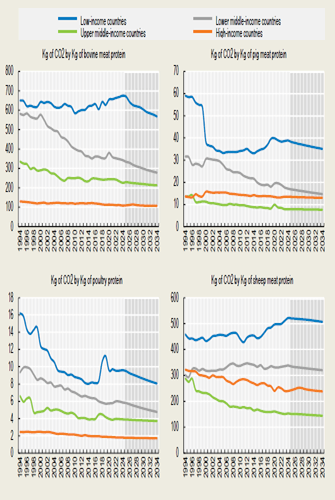

As such, while these interventions hold long-term promise, their implementation will depend on local capacities and infrastructure. Historic trends and projections of greenhouse gas emissions per kg of livestock protein (by income group and species) illustrate these dynamics.

The graphs below shows that in nearly all cases, except in low-income countries, there has been a downward trend in GHG emissions per unit of meat protein.

Emission reductions per protein unit in the last two decades have occurred at rates of -0.6% per year in high-income countries, -0.3% per year in upper-middle-income countries, and -1.6% per year in lower-middle-income countries and are expected to continue. Low-income countries experienced a rise (+0.6% per year) in emissions per unit of protein, highlighting opportunities for improvement expected to materialize during the period of interest.

The sizeable differences between income groups points to areas where productivity enhancements can substantially lower emission levels provided that enabling conditions are addressed.

As global food demand continues to rise, the challenge lies in reducing the environmental impact of agricultural production while simultaneously ensuring food security. This can be done by adaptation of large-scale emission reduction technologies (ERTs).

Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction Technologies

In agriculture, emission reduction technologies (ERTs) encompass a broad range of innovations, tools, and practices designed to lower greenhouse gas emissions from farming systems without compromising productivity. These include both biological and technical interventions that address the main emission sources in crop and livestock systems. The aim behind the implementation of these technologies is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions while maintaining or enhancing agricultural productivity.

Livestock Farming Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction Technologies

In the livestock sector, ERTs primarily aim to reduce enteric methane emissions, improve feed efficiency, and enhance manure management systems. Diet management plays a central role, with strategies such as optimized grazing to enhance pasture yield and quality, improved forage digestibility and precision ration balancing supported by artificial intelligence.

These approaches improve feed conversion efficiency and lower methane production during digestion. Feed additives such as 3-NOP and Bovaer, which are already authorized for use in the European Union, have proven effective in reducing emissions from ruminants, though their application remains challenging in the predominantly pasture-based systems in low- and middle-income countries.

The use of seaweed in ruminant diets offers further potential, although more research is needed to assess long-term impacts and scalability. Reproductive management, disease prevention and treatment, as well as selective breeding can also significantly reduce methane emissions by enhancing feed-to-emissions performance.

Technologies for improved manure management offer another important opportunity for reducing emissions. Anaerobic digesters capture methane from stored manure and convert it into renewable biogas.

Other technologies, such as solid-liquid separation, covered storage tanks, and optimized methods of manure application, help reduce direct methane emissions and nitrogen losses. Low-emission application techniques, such as dribble bars, have been shown to significantly reduce ammonia volatilization and associated indirect emissions.

Crop Farming Greenhouse Gases Emission Reduction Technologies

In crop production, ERTs focus on improving nutrient use efficiency, minimizing soil disturbance, and enhancing soil carbon sequestration. Precision agriculture offers significant opportunities in this context, enabling the targeted application of inputs using GPS-guided equipment, real-time sensors and machine learning.

Fertilizers and pesticides can be applied more accurately, reducing nitrous oxide emissions and limiting environmental runoff. Proper timing and methods of input application are also essential. Better synchronization of fertilizer and manure use with crop nutrient demand, alongside the application of nitrification inhibitors and variable rate technologies, can substantially reduce emissions and nutrient losses.

In addition to input management, various soil and landscape practices contribute to emissions mitigation and carbon storage. Conservation tillage and no-till farming help retain soil organic carbon, while the use of winter cover crops and buffer strips reduces erosion and nitrogen leaching. In wetland areas, restoring peatlands and rewetting organic soils present high-impact opportunities for long-term carbon sequestration. Other innovative solutions, such as agrivoltaics, are being explored to integrate solar energy

Limitations of Greenhouse Gases Emission Reduction Technologies Adoption

However, in spite of their technical potential, these technologies have seen limited adoption in many regions. Barriers to their adoption include high upfront investment costs, limited access to finance, inadequate infrastructure, lack of enabling policy frameworks or financial incentives and a general lack of awareness or technical support. Consequently, farmers often lack the means or motivation to implement such practices, especially in areas with restricted access to credit or advisory services.

Sources and References

- OECD calculations based on FAOSTAT-Emissions Totals, Statistical Division of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (accessed December 2024).

- FAOSTAT Emissions-Agriculture Database, OECD/FAO (2025),

- OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook

- OECD Agriculture statistics (database)

Share This Article: