Common Mutual Funds Investing Mistakes

December 15, 2025, 12:08 pm

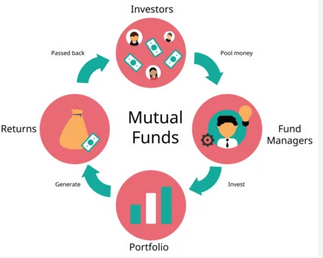

Mutual funds are financial vehicles made up of a pool of money collected from many investors to invest in a variety of securities, including stocks, bonds, money market instruments, and other assets.

Mutual funds are investment companies and they sell shares to the public which are redeemable on demand by the shareholders at net asset value.

HISTORY OF MUTUAL FUNDS

A purely American creation, the mutual fund was introduced in 1924 by a former salesman of aluminum pots and pans named Edward G. Leffler.

The mutual funds industry is now very large. There are thousands of mutual funds all over the world with trillions of dollars in assets under their management.

BENEFITS OF MUTUAL FUNDS

Mutual funds are quite cheap, very convenient, generally diversified, professionally managed and tightly regulated under some of the toughest provision of Federal securities law.

Mutual funds make investing easy and affordable for almost anyone. By so doing, mutual funds have brought millions of people into the investment mainstream—probably the greatest advance in financial democracy ever achieved.

TYPES OF MUTUAL FUNDS

There are different ways of classifying mutual funds. These ways are:

- Portfolio

In this category, funds are classified by the broad division of their portfolio. Based on their type of portfolio, mutual funds in this category are classified as follows

Balanced funds: If they have a significant (generally about one-third) component of their portfolio in bonds

Stock: If their portfolio is made up of nearly all common stocks

- Objective

In this category, the aim or vision of the mutual fund is what is used to classify them. Here we have majorly three types

Income: their primary is to earn revenue and pay them out as dividend to their shareholders

Price stability: their main objective is to keep up with inflation

Growth: their primary objective is capital appreciation – the increase of the value of their investment holdings

- Method of Sale

This category is distinguished by the way their shares can be traded and sold. We have major types in this category

Load: they add a selling charge (generally about 9% of asset value on minimum purchases) to the value before charges

No-load: they make no charge; their managements are content with the usual investment-counsel fees for handling the capital

COMMON MUTUAL FUNDS INVESTING MISTAKES

But mutual funds aren’t perfect. They are almost perfect and that word makes all the difference. Because of their imperfections, most mutual funds underperform the market, overcharge investors, create tax headaches and suffer erratic swings in performance.

Why don’t more wining mutual funds stay winners?

Migrating Managers

When a stock picker seems to have the Midas touch, everyone wants him—including rival fund companies. Most of the good stock pickers working at mutual funds tend to switch jobs a lot and after a while working for others, some of them move on to start their own mutual funds business

Asset Elephantiasis

When a fund earns high returns, investors notice—often pouring in hundreds of millions in a matter of week. That leaves the fund manager with few choices—all of them bad. He can keep that money safe for a rainy day, but then the low returns on cash will crimp the fund’s results if stocks keep going up.

He can put the new money into the stocks he already owns—which have probably gone up since he first bought them and will become dangerously overvalued if he pumps in millions more. Or he can buy new stocks he didn’t like well enough to own already—but he will have to research them from scratch and keep an eye on farm more companies than he is used to following.

No More Fancy Footwork

Some companies specialize in ‘incubating’ their funds, test-driving them privately before selling them publically. Typically, the only shareholders are employees and affiliates of the fund company. By keeping them tiny, the sponsor can use these incubated funds as guinea pigs for risky strategies that work best with small sums of money, like buying truly tiny stocks or rapid-fire trading of initial public offerings. If its strategy succeeds, the fund can lure public investors in mass by publicizing its private returns.

In other cases, the fund manager ‘waives,’ (or skips charging) management fees, raising the net return—then slaps the fees on later after the high returns attract plenty of customers.

Almost without exception, the returns of incubated and fee-waived funds have faded into mediocrity after outside investors poured millions into them

Rising Expenses

It often costs more to trade stocks in very large blocks than in small ones; with fewer buyers and sellers, it’s harder to make a match.

A fund with $100 million in assets might pay 1% a year in trading costs. But, if high returns send the fund mushrooming up to $10 billion, its trades could easily eat up at least 2% of those assets.

The typical funds holds on to stocks for only 11 months at a time, so trading costs eat away at returns like a corrosive acid. Meanwhile, the other costs of running a fund rarely fall—and sometimes even rise—as assets grow. With operating expenses averaging 1.5% and trading costs at around 2%, they typical funds has to beat the market by 3.5 percentage points per year before costs just to match it after costs.

Sheepish Behavior

Finally, once a fund becomes successful, its managers tend to become timid and imitative. As a fund grows, its fees become more lucrative—making its managers reluctant to rock the boat. The very risks that the managers took to penetrate their initial high returns could now drive investors away—and jeopardize all that fat fee income.

So the biggest funds resemble a herd of identical and overfed sheep, all moving in sluggish lockstep, all saying “baaa” at the same time. Nearly every growth funds owns the same companies. This behavior is so prevalent that finance scholars simply call it Herding.

Understanding why it’s so hard to find good mutual fund will help you become a more intelligent investor.

When you add up all their handicaps, the wonder is not that so few funds beat the index, but that any do. And yet some do. What qualities do they have in common?

QUALITIES OF MUTUAL FUNDS TO BUY

Below are some of the features of mutual funds that deliver good returns to their shareholders

Their managers are the biggest shareholders

The conflict of interest between what’s best for the fund’s manager and what’s best for its investors is mitigated when the managers are among the biggest owners of the fund’s share. When the managers own so much of the funds, they are likely to manage your money as if it were their own—lowering the odds that they will jack up fees, let the funds swell to gargantuan size, or whack you with a nasty tax bill.

They are cheap

One of the most common myths in the fund business is that “you get what you pay for”—that high returns are the best justification for higher fees. There are two problems with this argument. First, it isn’t true; decades of research have proven that funds with higher fees earn lower returns over time.

Secondly, high returns are temporary, while high fees are nearly as permanent as granite. If you buy a fund for its hot returns, you may well end up with a handful of cold ashes—but your costs of owing the fund are almost certain not to decline when its return do.

Since a mutual fund’s expenses are far more predictable than its future risk or return, you make them your first filter. There’s no good reason evert to pay more than these levels of annual operating expenses by fund category:

|

TYPE OF MUTUAL FUND |

EXPENSE RATIO |

|

Taxable and municipal bonds |

0.75% |

|

Equities (large and mid-sized stocks) |

1.0% |

|

Equities (small stocks) |

1.25% |

|

Foreign stocks |

1.50% |

|

High-yield (junk) bonds |

1.0% |

They dare to be different

An example is best to explain this. When Peter Lynch ran Fidelity Magellan, he bought whatever seemed cheap to him, regardless of what other fund managers own. In 1982, his biggest investment was Treasury bonds; right after that, he made Chrysler his top holding, even though most experts expected the automaker to go bankrupt; then in 1986, Lynch put almost 20% of Fidelity Magellan in foreign stocks like Honda, Norsk, Hydro and Volvo.

They shut the door

The best funds often close to new investors—permitting only their existing shareholders to buy more. That stops the feeding frenzy of new buyers who want to pile in at the top and protects the fund from the pains of assets elephantiasis. It’s also a signal that the fund managers are not putting their own wallets ahead of yours. But the closing should occur before, not after, the fund explodes.

They don’t advertise

Just as Plato says in The Republic that the ideal rulers are those who do not want to govern. The best fund managers often behave as if they don’t want your money. They don’t appear constantly on financial television or run ads boasting of their No. 1 returns.

Evaluating Mutual Funds Risk

Most mutual fund buyers look at past performance first then at the manager’s reputation, then at the riskiness of the fund, and finally (if ever) at the fund’s expenses. The intelligent investor looks at those same things—but in the opposite order.

Buying mutual funds based on their past performance is one of the stupidest thing an investor can do. Financial scholars have been studying mutual fund performance for over 50 years, and they are virtually unanimous on several points:

- The average fund does not pick stocks well enough to overcome its costs of researching and trading them

- The higher a fund’s expenses, the lower its returns

- The more frequently a fund trades its stocks, the less it tends to earn

Every mutual fund must show a bar graph displaying its worst loss over a calendar quarter. If you can’t stand losing at least that much money in three months, go elsewhere.

A leading investment research firm, Morningstar, awards "star ratings" to funds, based on how much risk they took to earn their returns (one star is the worst, five is the best). But just like past performance itself, these ratings look back in time; they tell you which funds were the best, not which are going to be.

Five-star funds, in fact, have a disconcerting habit of going on to underperform one-star funds. So first find a low-cost fund whose managers are major shareholders, dare to be different, don’t hype their returns and have shown a willingness to shut down before they get too big. Then and only then, consult their Morningstar rating

WHEN TO SELL MUTUAL FUNDS

Once you own a fund, how can you tell when it’s time to sell? The standard advice is to ditch a fund if it underperforms the market (or similar portfolios) for one to three years in a row. But this advice makes no sense.

The performance of most funds falters simply because the type of stocks they prefer temporarily goes out of favor. If you hired a manager to invest in a particular way, why fire him for doing what he promised?

By selling when a style of investing is out of fashion, you not only lock in a loss but lock yourself out of the inevitable recovery.

So when should you sell? Here are a few definite red flags:

- A sharp and unexpected change in strategy e.g. when a value fund starts buying lots of technology stocks

- An increase in expenses. This suggests that the managers are in their own pockets

- Large and frequent tax bill. This happens when the funds is trading excessively

- Sudden erratic returns.

[Ed. Note: Jason Zweig was a senior writer at Money magazine, a guest columnist at Time, and a trustee of the Museum of American Financial History. Formerly a senior editor at Forbes, he has written about investing since 1987. He has been a columnist for The Wall Street Journal since 2008]

Share This Article: