Foot and Mouth Disease Prevention

January 21, 2026, 8:54 am

Foot-and-mouth disease is a devastating animal disease that affects cattle, buffaloes, pigs, sheep, goats and various wildlife species.

Foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) does not affect humans. There is no health risk to humans from FMD; regardless, meat, dairy and animal products destined for human consumption should come only from healthy animal sources.

WHAT IS FOOT AND MOUTH DISEASE

Foot and mouth disease (FMD) is a highly contagious viral disease that mainly affects cloven-hooved livestock and wildlife. It’s debilitating effects on animal production, animal welfare, and trade in animals and animal products is immense and difficult to quantify.

Foot and mouth disease is endemic in parts of Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and South America, with significant progress reported toward eradication in South America. Foot-and-mouth disease has been eradicated from North America, some Pacific nations and Western Europe but outbreaks occur in these regions, periodically.

CAUSES OF FOOT AND MOUTH DISEASE

The viruses that cause FMD are among one of the most infectious agents known to veterinary or human medicine.

Foot and mouth disease virus (FMDV) is a member of the genus Aphthovirus in the family Picornaviridae. It has seven major serotypes: O, A, C, SAT 1, SAT 2, SAT 3 and Asia 1. Some serotypes are more variable than others, but collectively, they contain more than 60 strains.

While most strains affect all susceptible host species, some (e.g., the pig-adapted O Cathay strain) have a more restricted host range. Immunity to one FMDV serotype does not protect an animal from other serotypes. Protection from other strains within a serotype varies with their antigenic similarity.

Serotype O viruses have caused many of the recent outbreaks and incursions into FMD-free countries; however, any serotype can cause an outbreak, and multiple serotypes co-circulate in many endemic regions. While serotypes O and A are widely distributed, SAT viruses occur mainly in Africa, with periodic incursions into the Middle East, and Asia 1 is currently found only in Asia

SYMPTOMS OF FOOT AND MOUTH DISEASE

Animals affected by foot-and-mouth disease develop liquid-filled blisters on their feet, tongue, in and around the mouth, nose or snout, and on the teats. The blisters may rupture, leaving raw, tender skin exposed.

Pain and discomfort from the lesions lead to depression, loss of appetite, weight loss, and lameness, with animals unwilling to move or even to rise to their feet.

Older animals will suffer clinical signs for weeks before generally recovering. But younger animals – calves, lambs piglets – may die from foot-and-mouth disease due to sudden heart failure. In some regions, repeated infection leads to “chronic FMD” with permanent loss of health and productivity.

IMPACT OF FOOT AND MOUTH DISEASE

Though foot-and-mouth disease had been largely controlled in developed nations, in 2001, an outbreak in the United Kingdom spread to the Netherlands, with smaller outbreaks in France and Ireland, before being brought under control by widespread culling. The experience left its mark on the psyche of many of the farmers that lived through the tragedy: the UK alone suffered economic losses of more than $12 billion, and some 6.5 million sheep, cattle and pigs were slaughtered to halt the disease’s spread.

More recently, in India, direct annual losses due to foot-and-mouth disease are estimated at nearly $ 4.5 billion, in terms of animal deaths, measures to stamp out the disease and lost international trade in animals and animal products. The indirect losses – the harvests that don’t leave the farm for market because transport animals are sick, the crops that aren’t planted or seeds not sowed because animals can’t pull the ploughs, the cost of feeding animals that produce little or no milk and continue to lose weight – are much greater.

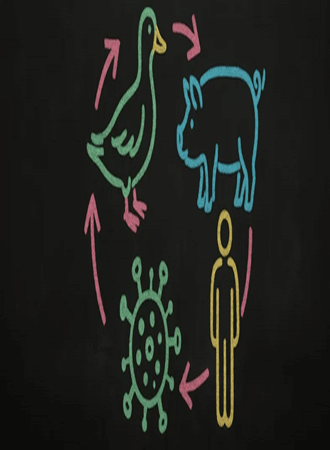

TRANSMISSION OF FOOT AND MOUTH DISEASE

Foot and Mouth Disease Virus (FMDV) can be found in all secretions and excretions from acutely infected animals including expired air, saliva, milk, urine, feces and semen, as well as the fluid from FMD-associated vesicles, and amniotic fluid and aborted fetuses.

Peak virus production usually occurs around the time the vesicles rupture and most clinical signs appear; however, some animals can excrete FMDV for up to four days before the onset of clinical signs, and those that develop subclinical infections1 can also shed the virus.

Foot and Mouth Disease Virus (FMDV) mainly enters the body by inhalation or ingestion, but it can also infect an animal through other mucous membranes or skin abrasions. Most animals are thought to become infected via direct or close contact, but local aerosol transmission can also occur within a farm. Cattle are particularly susceptible to aerosolized viruses, while pigs require much higher doses to be infected by this route.

Long distance airborne transmission may occasionally occur under favorable climatic conditions, with a few reports of FMDV spreading up to a hundred miles or more over water. Transmission over land is thought to be more limited, and rarely more than 10 km. Because pigs produce large amounts of aerosolized virus, the presence of large herds of infected swine may increase the risk of airborne spread. Transplacental transmission has been documented in sheep and cattle; however, one study indicated that FMDV is probably not transmitted by embryo transfer of washed bovine embryos.

Mechanical transmission by fomites and living (e.g., animal or human) vectors can also cause outbreaks; however, there is limited information on the survival of FMDV in the environment, with much of this information collected more than 50 years ago. Most studies suggest that, at temperatures of 20°C (68°F) or above, FMDV remains viable for a few days to a week or two, and occasionally up to a month, on (or in) various fomites, vegetation, soil or water, with some studies indicating that it may persist for long as 2-6 months at cold or freezing temperatures. The presence of organic material promotes longer survival. There are also a few outliers that remain to be confirmed, such as an old study that found this virus in dry hay at 22°C (72°F) after 20 weeks of storage.

How long animals can be infected from contaminated environments is still unclear. While FMDV has been reported to remain viable in stalls for 2 weeks, calves did not become infected in a recent study when they were placed in a room (18-20°C) that had contained infected animals 24 hours earlier, although viable virus was recovered from various sites in the room, with a half-life ranging from 3 to 7 days, and calves moved into the room without a waiting period became infected.

FMDV can sometimes persist for prolonged periods in meat, milk and other animal products when the pH remains above 6.0. It is inactivated by acidification of muscles during rigor mortis, but because the pH does not drop to this extent in some tissues, such as bone marrow and lymph nodes, it may survive longer when these tissues are also present. One recent study found that, while infectious virus could not be recovered from the muscles of euthanized pigs after 7 days of carcass storage at 4°C (39°F), it was isolated from the epithelium of vesicles on these carcasses for at least 11 weeks.

Older studies reported that, in animal tissues kept at 1-7°C (34-45°F), FMDV remained viable for 1-3 days in muscle, 7 months (but less than 12 months) in bone marrow, up to 4 months in lymph nodes, about 2 months in blood, 8-42 days in various internal organs (e.g., spleen, lung, stomach, kidney) and 8 days in dried hides. This virus is also reported to survive for 4-14 days in salt-cured bacon, tongue or sausages, 46-89 days in ham and a year in salt-cured hides.

PREVENTION OF FOOT AND MOUTH DISEASE

Foot and mouth disease (FMD) outbreaks in virus-free regions are usually controlled with standard stamping out measures (quarantines, movement restrictions, euthanasia of affected and exposed animals, and cleaning and disinfection). Good biosecurity measures should be practiced on uninfected farms to prevent entry of the virus.

People who have been exposed to FMDV may be asked to avoid contact with susceptible animals for a period of time, in addition to decontaminating clothing and other fomites. In some countries, vaccination may be used as an adjunct measure to help reduce the spread of FMDV or protect specific animals (e.g. those in zoos) during an outbreak.

Vaccines are also used in endemic regions to protect animals from illness. FMD vaccines are only effective against the serotype(s) contained in the vaccine. For adequate protection, the vaccine strains must also be well matched with the field strain. Raw tissues from animals that may be infected should not be fed to dogs, cats or other carnivores, as they may become infected or ill.

In FMD-free countries, import regulations help prevent this virus from being introduced in infected animals or contaminated foodstuffs fed to animals. Waste food (swill) fed to swine is a particular concern. Heat treatment can kill FMDV in swill; however, some nations have banned feeding swill to pigs due to the risk that this and other viruses may not be completely inactivated, for instance if parts of the swill do not reach the target temperature. Protocols for the inactivation of FMDV in various animal products such as milk products, meat, hides and wool have been published by WOAH.

In southern Africa, transmission from wild African buffalo has been controlled by separating wildlife reserves from domestic livestock with fences, and by vaccinating livestock. However, wildlife fencing may not be practical in some areas, and there are also some disadvantages to its use. Other species of wildlife do not seem to act as reservoirs for FMDV, but they may become infected and carry the virus to uninfected farms during an outbreak. The effects of FMD itself are also a concern in some wildlife species. Vaccination of livestock was reported to decrease outbreaks in some severely affected populations, such as saiga antelope

Foot and Mouth Disease Disinfection

Disinfectants reported to be effective against FMDV include sodium hydroxide, sodium carbonate, some acids (e.g., acetic acid, citric acid), sodium hypochlorite and accelerated hydrogen peroxide, as well as various commercial multi-component disinfectants such as Virkon-S.™ The disinfectant concentration and time needed can differ with the surface type, presence of organic matter and other factors.

Heat treatment of 67-68°C (153-154°F) for less than 10 minutes was reported to destroy viruses in fecal slurry, as well as spiked meat slurry (pH 6.6) used in making pet food, while viruses in homogenized bovine tongue epithelium from an FMDV-infected animal or an FMDV-spiked slurry and meal mix adjusted to pH 6.7 were destroyed within a minute at 79°C (174°F). FMDV is also inactivated at pH below 6.0 or above 9.0.

TREATMENT OF FOOT AND MOUTH DISEASE

There is no treatment for FMD only prevention and control.

Vaccination is an important tool used in controlling foot-and-mouth disease in many parts of the world. Yet it is a constant drain on resources, since effective vaccination requires a high proportion of animals to be vaccinated two or more times per year.

Vaccines are important to reduce disease, but to eliminate the virus, additional measures are essential to prevent virus transmission. These have added costs and require greater capacity to manage animal movements, including: strong surveillance mechanisms to detect infections; the ability to trace the origins and movements of infected animals; the capacity to implement quarantines; and either an emergency vaccination plan or the humane slaughter of infected herds, with proper disposal of animal carcasses by incineration or burial

SOURCES AND REFERENCES

Foot and Mouth Disease by Fiebre Aftosa

FAO FOOT-AND-MOUTH DISEASE FAQ

Share This Article: