RUGA Cattle Value Chain Opportunities

August 28, 2019, 12:17 pm

RUGA Cattle Value Chain Opportunities

History of Cattle Ranching in Nigeria

The main cattle production system currently in Nigeria and other parts of Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is the pastoral nomadic/semi-nomadic. However, several attempts to introduce European type of intensive cattle production systems such as ranching, feedlots and dairy farming were made during the colonial and post-independence era. These attempts were in the form of importation of purebred dairy cattle to establish dairy farms at Agege (1940) and Vom (1947), and establishment of Livestock Improvement and Breeding Centres (LIBCs) in many states for cross-breeding using exotic bulls and artificial insemination (AI) for increased milk production. There was also the introduction of semi-intensive managed feedlots using imported trypano-tolerant bulls and steers in South West Nigeria in the 1960s. In the 1970s, many Northern States established ranches for production of genetically improved weaners for small producers. Of note is the establishment of Mokwa Cattle Ranch (1972) in present day Niger state through German bilateral assistance. A similar ranch was also established in Manchok in present day Kaduna state. The defunct National Livestock Production Company (NLPC) first managed by the Nigerian Livestock and Meat Authority (NLMA) 1971-1976 and later in 1979 managed these ranches.

In addition, the World Bank and other development agencies have financed livestock projects. There were two World Bank assisted projects: the First Livestock Development Project (FLDP, 1974-1983) and Second Livestock Development Project (SLDP, 1986-1995). FLDP promoted ranching (parastatal and private) with imported trypano-tolerant Ndama cattle to establish Western Livestock Company in Oyo state. The project also provided credit for smallholder fattening schemes and supported research, training and marketing. The SLDP continued the successful smallholder fattening scheme, expanded ranching by establishing another Ndama cattle ranch in Adada in Enugu state and restocking the Oyo ranch. Newly introduced components were development of grazing reserves and settling of nomadic pastoralists, pilot cooperative dairy development and livestock systems research.

While the FLDP recorded success only in smallholder credit scheme, SLDP was assessed successful in increasing livestock production and the income of over 60,000 smallholder livestock producers directly, thus shifting the emphasis of public support to small traditional producers and contributing to poverty reduction in rural Nigeria (ICR No. 15769, June 21, 1996). Under the Ndama ranches programme, 1,341 in-calf heifers were imported and distributed to two ranches in Adada, Enugu state and Fashola, Oyo state. On completion of the SLDP, each of the 116 beneficiaries in the South East and South West of Nigeria, respectively, received 681 in-calf heifers in the form of a credit package of 4 heifers and a bull. To sustain the programme, the beneficiaries agreed to participate in an open-nucleus breeding network. However, while the open-nucleus breeding programme collapsed after loan closure in 1995, Ndama cattle and their crosses continued to exist and expand in these States and other places in Nigeria. Another positive contribution of this programme was that many beneficiaries entrusted their animals to settled pastoralists in their neighbourhood, thereby creating a strong bond between pastoralists and their hosts in these States. Another success story was a pilot cooperative dairy in Kaduna state. Under the Pilot Dairy Development Programme, about 1,900 farmers in the State were organized into ten registered cooperative societies with one apex cooperative federation – the Milk Producers Cooperative Association Limited (MILCOPAL).

The development of grazing reserves and settling of nomadic pastoralists was only partially successful due to poor management of common properties. At the close of the SLDP, 12 grazing reserves were gazetted and developed out of the 20 proposed; a total of 951km fire tracings were done; 74 dams were constructed; and 715 transhumant families were settled in seven grazing reserves. Other lessons learned through the projects provide further rationale for the current programme. FLDP and SLDP received a funding of $150m and remain the only FGN/World Bank intervention that accrued specifically to the livestock sector to date.

Although there are policies and strategic intentions at both national and state government levels to improve livestock production and agropastoral practices, these efforts have been hampered by many obstacles. The identified obstacles include: limited knowledge of Nigeria’s livestock assets by size and location; conflicts with nomadic pastoral/transhumance system due to feed, water and land insecurity; low productive breeds of livestock; income loss and adverse effects on human health due to pest and disease; and low income to farmers due to limited access to lucrative markets due, which is affected by the poor quality of produce, lack of standards and poor transport infrastructure.

In the same vein, inadequate institutional arrangements for policy and programme coordination have often led to duplication of effort and general inefficiency in resource use among agencies and ministries of the same government, between federal and state agencies and between states. Inadequate monitoring and evaluation arrangements for policy implementation has also led to situations in which policies and programs tended to lose sight of their focus and original goals without corrective measures being taken.

Similarly, private investors (both local and international) have not made full use of the comparative advantage and the opportunities in the livestock sector largely because of inadequate infrastructure, such as roads, energy, water and an unfavourable business environment, among others.

Many attempts were made in the past to establish ranches in different areas of Nigeria; however, these have been mostly characterized by failure and not sustained. The key lessons learned from these failures include:

- Land—lack of land titles was a major disincentive to pastoralist to develop land

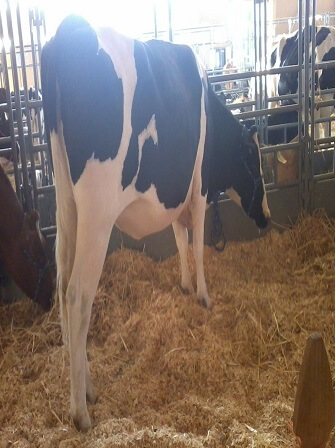

- Limited use of specialized cattle breed—resulting in poor milk yield and low weight gains of animals due to poor genetic makeup of indigenous breeds (For example, average milk yield of Holstein Friesian is 35-40L/day compared with 1-2L/day for Bunaji cattle, and average weight gain of Brahman cattle is 2.5kg per day versus 0.5kg for Sokoto Gudali cattle

- Lack of organized structured market of finished live animals and commodities (certified abattoirs and processing plants, standardization of animals and commodities for correct pricing regime etc.

Other lessons include poor transportation and logistics system for live animals (animal welfare) and cold chain products; absence of reliable and quality animal feeds; and lack of industrial bye-product supply chain for feedlots and dairy farms. There is also the lack of skilled manpower in areas of range management and farm management.

Cattle Ranching Success in Ethiopia

Ethiopia’s 57 to 60M cattle herd is the largest in Africa. Due to old practices, the herd has historically been underutilized for cash generation. Prior to the 2015 transformation effort, the productivity of the herd was limited due to a diet primarily based on forage and crop residue (86%), low levels of vaccination (only 30m of 57m), and a highly mobile ranching approach. As a result, the productivity of milk and beef remained acceptable standards. First, Ethiopian cattle produced low volumes of milk—1.34 litres/cow/day, compared to more than 30 litres/cow/day in the USA. Of the volume produced, only a very small proportion of the 3.1 billion litres of milk produced each year reaches commercial markets (about 150M litres/annum) due to a poor supply chain. Second, Ethiopian beef was of relatively low quality by USDA or global market standards due to the fact that Ethiopia tends to only process cows that are old by global standards (3-10 years old). That low volume was not helped by the fact that there were few modern abattoirs focused on beef exports.

To change this picture, investors and the Government of Ethiopia (via its 2015 Livestock Master Plan) intensified efforts to modernize practices across the cattle value chain by improving cross breeding to genetically raise the potential for higher dairy yields, increasing vaccination rates to broaden the herd’s survivability and market potential, and shifting feed and ranching patterns to produce a different type of beef suitable for exports as processed beef.

At the core of this initiative has been a new wave of private sector investors in the sector. One of such private investors, Verde Beef, was founded in 2014 with initial land holdings from the Ethiopian Government, which provided initial land grant in 2014 totalling 100 hectares for 35 years. In April 2015, an additional 1,000 hectares of land was granted by Government of Ethiopia. In its operation, it uses feed produced in-house: 60% grown nearby and 40% is purchased (maize, grain, oil cake, sulphur, lime and pre-mix). To process its cattle, it uses another company, Allana Group and Organic Export Abbattoir to slaughter, de-bone and vacuum pack, transport using cold chain infrastructure i.e. refrigerated truck to airport, cold room at airport, and then flown out. In 2014, Verde Beef processed 1,400 heads of cattle; by 2018, it is processing an estimated 18,000 head/annum. This example demonstrates both the prospects of catalytic national investments into the livestock transformation process, and the potential to merge small-scale agriculture into the livestock value chain, leveraging on multiple private sector partners.

Today, Nigeria’s livestock economy is relatively immature from a business process, technology content, and productivity perspective. It is a mirror image of Ethiopia’s sector in the early 2000s. In practical terms, that means Nigeria’s cows produce less meat and milk per unit of effort compared to global peers e.g. New Zealand, Argentina, Brazil and the United States. While elements of this is due to genetic endowment, the bulk of the sub-optimal outcome is due to poor management practices in the form of poor feeding, excessive physical stress on the cattle from continuous movement and lack of water, and inefficient processes.

These are relatively easy to fix challenges. By investing in improved feed, watering and processing systems, productivity can rise sharply. For example, a typical U.S beef cow is bred on a ranch and is not permitted to trek hundreds of miles. Upon reaching a weight of 850kg- 950kg and above, the cow is slaughtered for processing. The meat produced is appropriately tender, reflecting a balanced mix of fat and muscle. By comparison, a Nigerian cow and by extension the value chain for livestock, suffers some of the following disadvantages:

Productivity: Cattle go to market for slaughter at an average weight of 250kg at 2-3 years resulting in more expensive beef per kg versus imported peers. Nigerian beef today is among the most expensive in the world at approximately $6/kg versus $4/kg in the Netherlands and $2.5/kg in India. Restructuring the meat production ecosystem will result in improved access to meat-based proteins at more competitive price points for Nigerians

Processing: Low quality processing of slaughtered cattle reduces the potential realizable value of cattle. It is estimated that an improvement in facilities, including modern meat processing, will boost realized values by 25%-40% due to a boost in value added products

Supply Chain: Reduction in the number of middle men by shortening the distance between ranchers and meat processors will boost the profitability of cattle farmers and ranchers.

Solving these issues will result in a boost for the broader Nigerian economy. There are several steps that can be taken. For example, one model of change involves building a modernized livestock supply chain with more proximately situated slaughter houses. These processing plants will be co-located with feedlots where cattle are fattened to boost income and job growth.

Cattle Production Value Chain

Value chains are the linked group of people and processes by which a specific commodity is supplied to the final consumer. These chains have inputs that are used to produce and transport a commodity towards a consumer; this is the supply chain. The value chain encompasses more than the production process; value chain as a term implies a low of information and incentives between the people involved. Money is sent from the consumer to the different people in the chains to complete the value chain.

The figure above describes a typical livestock value chain, and provides a broad characterization of the main areas for investment opportunities, that can lead to a modernization along the value chain. The application of a value chain approach to this pillar considers the various steps in the livestock business, from supply of quality inputs to livestock farming, postharvest handling and agro-processing. The goal is to consistently deliver high quality, nutritious and safe meat, dairy and other value-added animal products to local, regional and international markets. The incorporation of downstream value-addition creates further job opportunities and access to nutritious food in the local communities. For example, management of the relative costs from an early stage to slaughter ready calves is a key drive of profitability. For example, land development costs on a per hectare basis matters, as does the cost of acquiring pregnant heifers, or young calves, and of course the cost of fattening to production values.

Investment Areas

Input Supply

The success of any livestock enterprise depends on adequate supply of quality inputs. Pastures supply the cheapest source of feed for ruminant livestock. The NLTP (National Livestock Transformation Plan) proposes the adoption and integration of sown pastures into the livestock sector, as a strategy that will ameliorate most of the conflicts being experienced and make livestock production more profitable and more attractive. In addition to pasture, which can be grazed or cut for hay or both, silage (made from maize mixed with legumes) will be necessary for the dairy component of NLTP, because silage is one way that fresh vegetative material can be conserved for use during the dry season in environment like Nigeria. This helps to reduce the cost of supplementary feed for milking animals while increasing their milk production.

Access to land will be provided in gazetted grazing reserves already embarked by the frontline States, as well as privately purchased or leased land assets. Accompanying access to land, would be infrastructure access/upgrades, which would include the provision of roads, power, water, information and communication technologies, drainage, fencing etc.

Water supply will include rainwater harvesting, storage and distribution, dams and boreholes. States will play a critical role in accelerating the formation of livestock value chains if they negotiate investment agreements that bifurcate the role of the state and private investors accordingly; that would enable each party to do what it does best to accelerate the creation of jobs, capital assets and trained personnel.

Another core input will be the provision of special credit packages, concessionary access to specialized inputs like veterinary drugs, vaccines, equipment etc. as well as logistics and common infrastructure to support their operations within the reserves. A sanitary mandate program that carves out specific areas for private animal health service providers will ensure competitiveness, growth and sustainability of animal health delivery within and outside the grazing reserves. Given the scale up in the sector, it would be useful to consider alternate operating models for assets such as the Vom Laboratory given the sheer volumes of vaccines and related medicines that need to be produced.

Labour would include human resources in the form of administration personnel and technical staff, in the case of ranch operations. Other inputs will include veterinary services such as diagnostic laboratory; insurance, banking, schools and other social services extensions.

Production

The livestock production and management system will be anchored on the selection of suitable breeds, facilities for artificial insemination and establishment of livestock management system including traceability. It will also include the establishment and management of pasture and fodder production, harvesting, conservation, storage and utilization. Areas will be set aside for crop productions only (such as maize) as source of food for humans and supplementary feed to support livestock production. Equipment and machinery for land clearing, land preparation for pasture and crop production, irrigation, application of agrichemicals, harvesting, baling, storage (hay barns) and transport. A workshop will be built and operated to service and repair machinery and equipment.

A robust disease control and surveillance programme for cattle and other ruminants will form part of the production value chain in order to mitigate the risk of disease and pest occurrence in clustered settings within and outside the grazing reserves. The provision of a comprehensive animal health package to improve productivity in the selected states will be carried out primarily as a public good. This will enhance food safety to protect humans and facilitate international trade. The private sector will therefore be enabled to play a major role in delivery of veterinary services.

A comprehensive livestock identification and traceability system (LITS) will be established and operated in the designated areas and nationally by using unique identifiers and registration systems to identify animals individually and/or collectively. This will support livestock movement control, disease surveillance, public health interventions with specific emphasis on zoonoses and food safety as well as trade and security of livestock.

Product Collection, Handling and Processing

At the level of crop production, this will include provision of equipment for grain drying, grain store, hay barn, feedlot; whereas it will include refrigerated storage (cold rooms, freezers) at the level of livestock products. Pasteurisation is required in the case of milk products. This will decrease rates of spoilage, increase the distance producers can travel thereby expanding market access, and hence decrease the frequency of sales at less than optimal prices. This whole process also flows into processing, which also requires refrigerated storage (cold rooms, freezers), packaging, quality control and setting quality standards.

Crosscutting the value chain will be research, and this will be undertaken at each level of the chain. It will allow a better understanding, and hence necessary improvements, around inputs, production, collection, processing as well as marketing of livestock products as well as other related activities.

Strategic Priorities for Economic Investment

Securing natural resources—land, water, feed

The input supply value chain through gazetted grazing reserves will ameliorate the challenges around access to resources and mitigate conflict. Ensuring that non-gazetted reserves are gazetted, will also ensure increased access to resources for cattle production. Incentive schemes for private landowners to engage will be investigated.

Sustainable models for ranching must be developed

The development and testing of different models of ranching involving various combinations of value chains, be it beef or milk production will lead to evolving different types of ranching models. This will eventually lead to the gradual modernization of the cattle production systems through appropriate ranching practices, which could include aspects of breed improvement through artificial insemination embryo transfer to increase milk and meat yield of local cattle breeds. It will also contribute to the gradual transition from migratory and extensive cattle breeding and rearing practices to a more sedentary cattle breeding and rearing practices, again contributing to mitigating conflict.

Infrastructure needs for ranches will be met—roads, electricity, fencing

On the back of developing ranching models, and meeting resource needs, is also the need to develop complementary infrastructure. Critical infrastructure of road, electricity and fencing will ensure security especially for cattle and will particularly make the grazing reserves attractive to cattle herders.

Other support services must be developed—transport, health, education

Other support services are required to complement infrastructure, and are particularly critical because cattle herders will be encouraged by the presence of health and educational facilities, in addition to robust infrastructure. Having a good transport network will provide the confidence to herders that they can easily get their meat and milk products to the market.

Stakeholders must develop a deeper understanding of value chains—from input supply to marketing

An understanding of the flow of materials through the value chain is important in understanding how each point of the chain functions; bearing in mind that value chains involve several products, including waste and by-products. This understanding would include production and risk issues such as disease, and would engender an understanding of the flow and distribution of incentives along the chain and how to manage those risks.

Private Sector Investment is encouraged

Recognizing that government alone cannot possibly undertake all the investment initiatives, the private sector will be critical in investing in areas such as infrastructure as well as aspects of the value chain such as marketing and processing

Enabling policy and legislative environment will be put in place—in support of value chains

Enabling policies around access to land, credit facilities, and private sector involvement are critical to the proper implementation of the plan, and would drive investment opportunities along the value chain. In the medium term, supportive and enabling legislation around the national livestock system should be developed at both federal and state level.

You can begin your journey to taking advantage of the cattle farming business opportunities that NLTP will create by learning more about cattle and livestock farming productivity. Sign up to watch our tutorial videos on cattle farming health and productivity in order to be ready to take advantage of the NLTP opportunities today.

And if you need a business plan to guide you and help you get funding for milk production and beef processing, send an email to agsolutions@agricdemy.com

Share This Article: